Grief rarely follows a predictable path. People respond to loss in deeply personal ways, shaped by memory, attachment, and circumstance. For artists, grief often becomes something tangible. It turns into sound, form, or material, allowing loss to exist without needing to be explained or resolved.

When a 65-year-old oak tree in Steve Parker’s front yard died from oak wilt, he chose not to treat it as waste. The tree had sheltered migratory birds for decades, and its presence was woven into daily life. Parker cut the trunk into cross-sectional slices and carved grooves directly into the wood, transforming them into playable records. He built a custom record player designed specifically for these wooden discs, which are displayed like artifacts behind the turntable. Etched into the wood are the songs of birds that once nested in the oak. When played, the sound is rough and uneven, shaped by cracks and warping in the live oak. Those imperfections are intentional, preserving the tree’s character rather than smoothing it away.

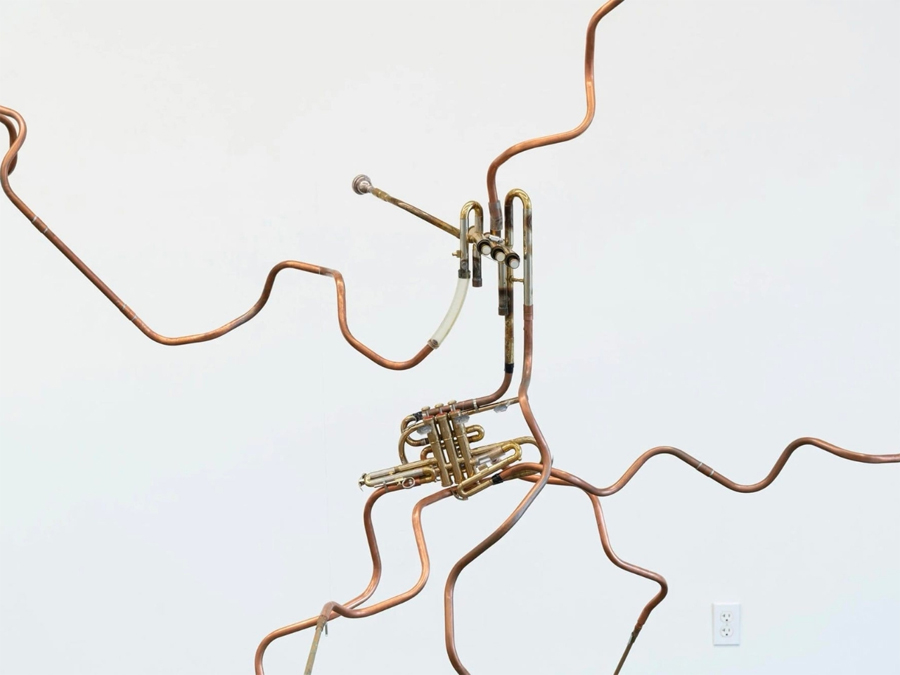

The project expanded into a second work titled “Sheng Shrine.” Built from salvaged brass valves, copper tubing, and breathing bags, it is animated by CPAP machines and ventilators. These machines push air through discarded Chinese shengs, traditional mouth organs associated with life and renewal. The resulting sounds include mechanical clicks, labored airflow, and reedy tones that feel both artificial and emotional. Parker collaborated with sheng virtuoso Jipo Yang to interpret the bird calls and shape them into short compositions.

As the work evolved, Parker recognized a deeper connection. His grief for the tree echoed the loss of his father to cancer, a slow decline marked by attention to breathing and comfort. The same medical devices once associated with life support now give breath to silent instruments, playing songs for a dead tree.

What makes “Funeral for a Tree” resonate is that it allows the loss to speak for itself. The tree becomes the instrument, the birds become the music, and breath continues through mechanical means. Rather than offering closure, the work creates space for memory, absence, and sound to coexist, turning grief into something that can still be heard.