In the early 1980s, London wasn’t exactly a hopeful place. The city was gripped by deindustrialization, unemployment, and the aftershocks of Thatcher-era policies. The punk movement had come and gone, but its energy still lingered in the air – you could feel it in music, in fashion, and in design. That’s the world Ron Arad stepped into when, in 1983, he created the Concrete Stereo.

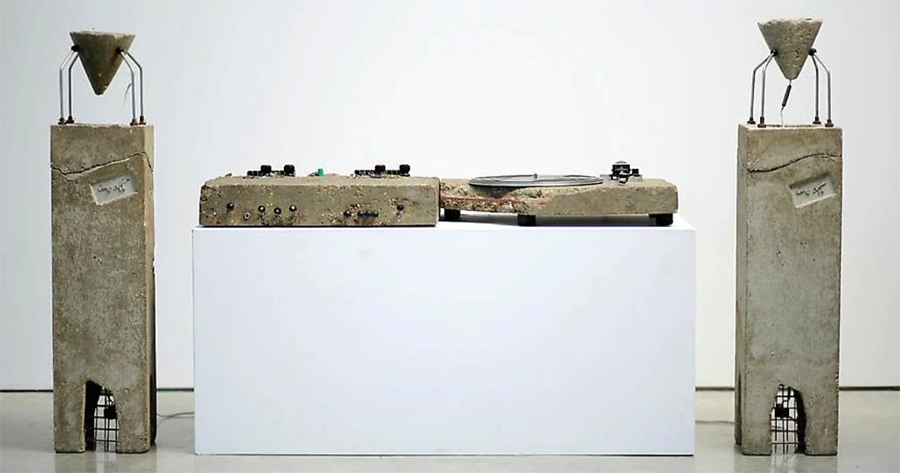

At first glance, it looks absurd. A stereo system – turntable, amplifier, and speakers – completely encased in raw, grey concrete. Not decorative concrete. Not concrete polished to mimic stone. Just rough, heavy, unpainted, with rebar exposed and the corners chipped. It looks like it came from a bombed-out building. And that’s the point.

Ron Arad wasn’t interested in beautiful surfaces or polite design. He wanted to provoke. The Concrete Stereo isn’t about pristine sound quality or user-friendly knobs. It’s about forcing the user – and the viewer – to think differently. The sound doesn’t pour out, it struggles. The concrete swallows part of the audio, creating a muffled, physical tension between the music and the object that delivers it. You hear it, but you also feel it fighting to be heard.

It was a brutalist manifesto in physical form. Arad was reacting not just to design norms, but to the polished consumerism that defined much of the 20th-century electronics industry. Sleek plastic, glossy wood veneer, brushed metal – all those signals of refinement were tossed aside. Instead, he gave us mass, density, and friction.

Only ten of these Concrete Stereos were ever made. They’re not just rare – they’re iconic. Five now live in museums: the V&A in London, Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, SFMOMA in San Francisco. The other five are in private hands. One of them sold for nearly £50,000 at Christie’s in 2019. But even if you had the money, it’s not the kind of stereo you’d casually add to your living room. It demands its own space – physically, visually, and conceptually.

Arad didn’t stop here. His later works – including twisted steel chairs, deconstructed bookshelves, and experimental architecture – continued the same conversation: where does design end and art begin? And more importantly, why do we try so hard to separate them?

The Concrete Stereo doesn’t try to be lovable. It doesn’t try to make you comfortable. But it succeeds in doing something most industrial design never dares: it tells the truth. About materials. About culture. About sound as resistance.

This isn’t a stereo you listen to while multitasking. This is a stereo you confront.